By Andy Harig, Vice President, Tax, Trade, Sustainability & Policy Development, FMI

Economists – still stinging after more than 170 years from Thomas Carlyle’s designation of their craft as “the dismal science” – often resort to pop culture clichés to describe otherwise dry and complicated subjects. If you’ve tuned into the news over the past four months, you’ve no doubt witnessed economic circumstances described as “a perfect storm” or heard cautions about “flashing red warning lights.” With July CPI numbers in, and inflation dropping off of 40-year highs, some economists are resorting to another old favorite, “What goes up must come down!”

This must be true, right? The concept is, after all, positively Newtonian. But it also glosses over the complex factors that impact food prices.

Many of the current challenges facing the economy as a whole have been aggravated and accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. But the recent increase in grocery prices is not something that simply happened overnight or that is entirely pandemic related. As Dr. Ricky Volpe, professor of agribusiness at Cal Poly, writes in this excellent piece explaining the complex web of factors impacting food prices, to completely blame COVID would be to ignore the cumulative effects of structural issues that have been challenging the food industry for years.

Recently, Dr. Volpe and I hosted a briefing for food industry stakeholders and Congressional staff to explore some of the factors that influence the recent rise in food prices. Even when inflation starts to slow and level off (as we may be witnessing), the elevated cost of “black box” inputs like energy, labor, transportation, and packaging take time to recalibrate. Unfortunately, this means that food prices may remain higher in the short-term even as inflationary pressures start to ease.

Energy

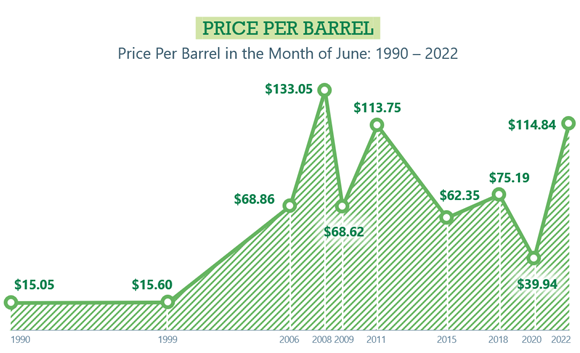

Over the last two decades, volatility in the price of fuel has increased dramatically, transforming a relatively steady cost input for manufacturers and retailers into a fluctuating variable, driving price swings that dramatically impact every aspect of the cost of the products on grocery store shelves. As you can see from the chart to the right, oil prices have been on a rollercoaster ride since the turn of the millennium.

Labor

Labor has also posed a significant challenge for the food industry. According to an FMI survey, 80% of respondents said their inability to attract and retain quality employees is having a negative impact on their businesses. While the pandemic certainly exacerbated the labor shortage, a lack of critical workers, such as truck drivers, has been building for decades. According to the American Trucking Associations, a driver shortage of just under 20,000 in 2012 hit an industry high of 80,000 in 2021; this driver shortage is projected to double again to 160,000 by 2030.

Transportation

In addition to a growing shortage of actual truck drivers, there is also a shortage in truck capacity, which has driven up transportation costs upward. Since the start of 2019, there has been a 55% shortage in refrigerated trucking capacity, while long-haul trucking rates have increased 61% on a per mile basis.

Packaging

Food packaging is a double-edged sword for the industry. On the one hand, packaging has helped to decrease costs as innovations have made food more storable, transportable, and durable. On the other hand, packaging is energy intensive, and increased fuel costs coupled with challenges such as differing state regulations have also significantly increased food packaging costs over the last two decades.

Innovative Solutions

The good news is that innovations and efficiencies driven by American food producers have helped to keep food costs lower than in many other nations. Modernization in sectors like farming, manufacturing and transportation have made food production and storage more efficient and cost-effective. In fact, when expressed in constant dollars, many foods are more affordable today than they were 30 years ago even with the spike in inflation.

Investments in creative new approaches like vertical farming, renewable energy, artificial intelligence (AI) and automation will help address some of the industry’s long-term structural issues. For example, vertical farming can help to cut down on supply chain inefficiencies by growing produce closer to where the products will be sold, reducing transportation time and costs, and protecting crops from volatile weather environments. The adoption of AI in food transportation can enable logistics managers to reduce dwell time – the periods truck drivers spend waiting to drop off or pick up product – and improve the ability to forecast availability and increase efficiency across the transportation supply chain.

All of these solutions should offer us a measure of optimism that, even though food prices are higher today, the food system will continue to become more efficient and productive, thereby keeping food prices in check over the long haul.

Industry Topics address your specific area of expertise with resources, reports, events and more.

Industry Topics address your specific area of expertise with resources, reports, events and more.

Our Research covers consumer behavior and retail operation benchmarks so you can make informed business decisions.

Our Research covers consumer behavior and retail operation benchmarks so you can make informed business decisions.

Events and Education including online and in-person help you advance your food retail career.

Events and Education including online and in-person help you advance your food retail career.

Food Safety training, resources and guidance that help you create a company food safety culture.

Food Safety training, resources and guidance that help you create a company food safety culture.

Government Affairs work — federal and state — on the latest food industry policy, regulatory and legislative issues.

Government Affairs work — federal and state — on the latest food industry policy, regulatory and legislative issues.

Get Involved. From industry awards to newsletters and committees, these resources help you take advantage of your membership.

Get Involved. From industry awards to newsletters and committees, these resources help you take advantage of your membership.

Best practices, guidance documents, infographics, signage and more for the food industry on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Best practices, guidance documents, infographics, signage and more for the food industry on the COVID-19 pandemic.