By: Adam Friedlander, Specialist, Food Safety and Technical Services, Food Marketing Institute

While the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 (FSMA) has updated U.S. food safety regulations, an emerging technology, known as whole genome sequencing (WGS), is revolutionizing outbreak investigations to more rapidly identify and prevent pathogenic bacteria from entering our food supply.

While the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 (FSMA) has updated U.S. food safety regulations, an emerging technology, known as whole genome sequencing (WGS), is revolutionizing outbreak investigations to more rapidly identify and prevent pathogenic bacteria from entering our food supply.

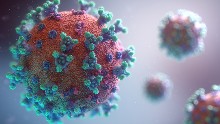

Whole genome sequencing is a microbiological testing procedure which determines the order of bases in the genome of an organism – think DNA fingerprint analysis for bacteria. The sample is plated, purified, sheared, copied and sequenced into a computer analyzer to map out the genome. The organism’s identity is discovered through a computer program, which assembles millions of DNA reads into the correct order, similar to a jigsaw puzzle. Once complete, the collected data are entered into private and public databases, known as PulseNet and GenomeTrakr, respectively, where further analysis is required to identify specific pathogenic strains and genetic traits.

In 1996, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began using Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) to investigate outbreaks through PulseNet. Although this technology helped public health officials solve some of America’s most deadly outbreaks, whole genome sequencing produces more accurate, rapid and cost-effective results. For this reason, the CDC has stated that WGS will replace PFGE as “the new PulseNet gold standard for subtyping pathogens that cause foodborne illness” in 2018.

According to a 2011 CDC publication, more than 9.4 million incidences of foodborne illness were reported from the 31 major pathogens. Of these cases, 56,000 were hospitalized and 1,350 died from illnesses directly linked to foodborne pathogens. Symptoms of infection from foodborne pathogens range from relatively mild (such as nausea, diarrhea and fever) to life-threatening. While infants, the elderly, pregnant women and persons with weakened immune systems are most susceptible, pathogenic organisms pose tremendous risk to the entire population.

On May 22-23, 2017, the Institute for Food Safety and Health (IFSH) hosted a symposium, Whole Genome Sequencing for the Food Industry: Current Procedures, Advances, Obstacles and Solutions, in Burr Ridge, IL. Speakers from government, academia and industry shared cutting-edge research, best practices for environmental sampling, and hurdles associated with analyzing large data sets. This conference demonstrated how government agencies are committed to developing practical policies alongside industry leaders to improve WGS surveillance.

It is important to note that WGS will be used in conjunction with other tools by regulatory agencies for outbreak investigations. Focusing resources on proper cleaning and sanitation protocols, good manufacturing practices (GMPs) or good retail practices, and comprehensive food safety training are the most effective strategies to combat foodborne illness. As WGS technology continues to advance, further research is critical to identify bacterial strains and genetic traits, while reducing foodborne illness and outbreaks across the supply chain.

For more food safety information, visit www.FMI.org/FoodSafety.

Industry Topics address your specific area of expertise with resources, reports, events and more.

Industry Topics address your specific area of expertise with resources, reports, events and more.

Our Research covers consumer behavior and retail operation benchmarks so you can make informed business decisions.

Our Research covers consumer behavior and retail operation benchmarks so you can make informed business decisions.

Events and Education including online and in-person help you advance your food retail career.

Events and Education including online and in-person help you advance your food retail career.

Food Safety training, resources and guidance that help you create a company food safety culture.

Food Safety training, resources and guidance that help you create a company food safety culture.

Government Affairs work — federal and state — on the latest food industry policy, regulatory and legislative issues.

Government Affairs work — federal and state — on the latest food industry policy, regulatory and legislative issues.

Get Involved. From industry awards to newsletters and committees, these resources help you take advantage of your membership.

Get Involved. From industry awards to newsletters and committees, these resources help you take advantage of your membership.

Best practices, guidance documents, infographics, signage and more for the food industry on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Best practices, guidance documents, infographics, signage and more for the food industry on the COVID-19 pandemic.